Without Supervision

There comes a point when you are on your own.

Wednesday, November 26, 2025

Where's the Love?

Saturday, October 4, 2025

Upcoming Birthday

Tomorrow's my 67th birthday. Our final decree of "absolute divorce" is pending the judge's signature. I asked Liz what she wanted for her birthday dinner, back in March, so I could get the ingredients I'd need to make it. Completely forgetting that, she later said she wanted to go to Honey Pig, referring to my plan to make it for her at our house as "some fantasy of his." So we went to Honey Pig. (Fine by me, really. I like Honey Pig.)

So we're not going anywhere, I guess, and most likely she's not going to make me anything, as she hasn't asked me what I want. As I rather thought when she first brought it up, this "we'll stay friends" thing was so this process would be easy on her.

I would have liked to go to Honey Pig with my friend again, though.

Tuesday, September 23, 2025

A Better Day

Monday, September 22, 2025

Today

Thursday, May 22, 2025

And a Lesson Passed On

Another professor from my college days passed away recently. This one was a really decent guy. His name was Norton Starr.

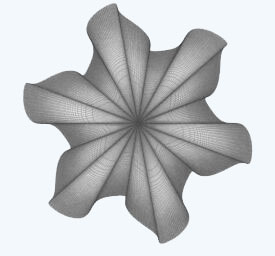

He mostly worked with a pen plotter, which draws lines on paper with a ballpoint pen. Those fell out of use for a long time, as laser printers got faster and were able to draw finer lines. Lately, they've been making a comeback because the esthetics of the actual mechanical system's output are gentler on the eye than razor-sharp laser print. He developed a family of shapes based on modulated radial patterns, which are now called "Starr Roses." Here's an early one:

In the 1970s, these could take an hour to draw. Today, we can draw them in a split second and, owing to that fact, we can draw them repeatedly, in rapid succession, allowing us to animate them (here's an example I created).

Prof. Starr taught me how to make these shapes in 1977. Today, I teach my students how to make them. I sent him an email, about six months ago, to let him know his work was still in classrooms, exciting new undergraduates, 50 years after he first produced it. He sent me a nice note back, seeming pleased by what I'd told him. I'm glad I did, when I did, because he passed away a few weeks later, at the age of 88.

Norton Starr may be gone, but I'm making sure that the fun and joy I had with math and art he showed my generation is passed on to the next generation after mine. Here's hoping the Starr Rose lasts forever.

Rest in Permanence, Professor.

Monday, March 10, 2025

Lesson Learned, Lesson Taught

Found out a professor of mine from my college days passed away a few years back. I'm a university instructor now myself. Not formally a "professor," but the students all call us that, no matter what our title on the paper says. My style as an instructor is very much due to having been that past professor's student, long ago.

A couple of years ago, a student came into my office with a fried Arduino in his hand. He'd hooked up the power wrong, based on some dumb YouTube he'd seen. Did I kick him out? No. I spent two days a week for the rest of the term, teaching him basic electronics. He knows what he's doing now, and he doesn't think I'm an asshole.

What would have made him think I'm an asshole? I suppose if, instead of helping him see what he'd done wrong, I'd castigated him for misusing equipment, told him he was too ignorant to work with electronics gear, and banned him from my lab, that might have done it. But I didn't because, thanks to that professor of mine, I know what it feels like to be treated that way, so that's not what I did.

Rest in peace, professor.

You were a dick to me. But, I finally got even with you for it. When I was in your place, and a young adult came to me after making a mistake, I undid the damage you almost did to the future. As far as my student is concerned, it's the same as if you were never here.

Monday, December 9, 2024

Standing for the Anthem

My wife and I go to sporting events at the university where I work. Each one starts with a playing of the national anthem, after the announcer says we should stand and, among other things, show respect for the people who defend our nation.

Our anthem is not a military anthem. As a military brat, I learned to stand when it is played. But not for our military. I stood because military brats stand for the anthem.

The announcer also says we should place our hands over our hearts. I don't do that either. The hand-over-heart is called the "civilian salute." As a military brat, I know that there is no civilian salute. That's part of what it means to have a country where the military is under civilian control: there is no paramilitary regimen that the civilians must obey. Further, the salute is a military privilege. Civilians aren't entitled to it. So I don't do it.

I do stand. When the music ends, I blow a kiss and give a short military salute to the sky. (As it happens, I have a DD-214, so I actually can salute in this context, under the silly law Republicans passed to make it look like the flag is some kind of sacramental object.) But I do this to thank my mom, and honor my dad, who was a lifetime military officer.

Yes, I do stand for the anthem. Not for the nation I have loved. Not for our fighters who defend it. I stand for the memory of who my parents raised me to be. I am a military brat. We stand.